Resources by Program Type

All Standalone certificates at Texas A&M International University submit annual assessment documentation. As compared to degree programs, some of the distinguishing characteristics of certificate programs pose challenges to intentional and meaningful assessment of student learning.

Because of differences in how certificate programs are managed and organized within different school and colleges, there is not a "one size fits all" strategy for certificate assessment. The guide linked below was created to help facilitate internal discussions about intentional planning of learning outcomes assessment in certificate programs.

-

One purpose of program assessment is to determine what students know and what they can do by the time they graduate. Many program assessment plans make use of end-of-experience measures to capture this information. In undergraduate programs these measures might include capstone projects or final portfolios. In graduate programs, such measures are typified by thesis/dissertation documents and final defenses (or final presentations for non-thesis options). However, graduate faculty committees do not typically allow students to progress to the defense or final presentation stage unless they are confident students will succeed at a certain level. This calls into question how meaningful these data are for the purpose of identifying how student learning could be further improved.

Instead of focusing solely on end-of-experience measures, graduate programs should measure student learning over the course of the program. Strategies include:

- Annual evaluations: A standardized evaluation survey or rubric that includes all key program learning outcomes (PLOs), this measure can take on various formats including qualitative response forms. Evaluations may be completed by advisors/committee chairs who are very familiar with the student and their work. Alternatively, external reviewers are sometimes asked to provide a potentially less biased evaluation. In the latter case, especially, it is crucial that reviewers are supplied with examples of student work.

- Course-embedded assessments in key courses: Graduate coursework is more customized as a student progresses through the program, but most programs require students to take a core set of courses within the first year or two. Utilize (perhaps already existing) embedded assignments/projects in these courses to evaluate program learning outcomes.

- Brown Bag seminars or symposiums: Institute a monthly or bi-monthly event and invite students to present articles, manuscripts, literature reviews, or current research projects. Faculty can record quantitative or qualitative observations during the presentations. If the school, college, or University hosts periodic poster symposiums, this is an excellent place to evaluate visual and oral communication skills.

- Developmental portfolios: This type of portfolio includes student work from all stages of the program, showing learning progress and growth over time. It may include drafts or iterations of student work. Faculty work together to determine how to best evaluate these portfolios.

- Comprehensive/preliminary exams: These are robust evaluation tools which can provide insight into a number of key PLOs all at once. As the last major milestone before work on the dissertation begins, these measures may provide valuable information about student readiness.

- Supplement with indirect measures: Periodically surveying students about their own perceptions of how well they are demonstrating and achieving PLOs may provide valuable information, particularly when compared to findings from direct measures.

The Value of Graduate Program Assessment

At the annual meeting of the Council of Graduate Schools in Washington in 2010, a panel of deans led a workshop on learning outcomes assessment and its value for improving graduate programs. They were asked:"In doctoral programs with intense mentor-apprentice relationships, the idea of establishing rubrics and other lists of learning outcomes might seem off-key. If I'm a senior professor...and I've supervised 30 dissertations during my career, I probably know in my bones what successful learning in my program looks like. Why should I be asked to write out point-by-point lists of the skills and learning outcomes that my students should possess?"

This is how they responded:

Charles Caramello, Associate Provost for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Maryland: If you write out lists of learning outcomes, you're making the invisible visible...We've all internalized these standards. They're largely invisible to us. Assessment brings them into visibility, and therefore gives them a history.

William R. Wiener, Vice Provost for Research and Dean of the Graduate School at Marquette University: There's no way to aggregate and to learn unless you've got some common instruments. By having common instruments, we can see patterns that we couldn't see before.

Charles Caramello: Faculty care about standards. They really care about excellence. They really care about evaluation, and they really care about peer review. To the extent that you can say, Look, assessment is a form of all of these things--it's not alien to what you do every day. It's another name for it, and a slightly different way of doing it. And the great advantage of it is that it gives you a way to aggregate, and therefore see patterns.

Quotes taken from the article "Measurement of 'Learning Outcomes' Comes to Graduate School' by David Glenn, published by the Chronicle of Higher Education in December 2010.

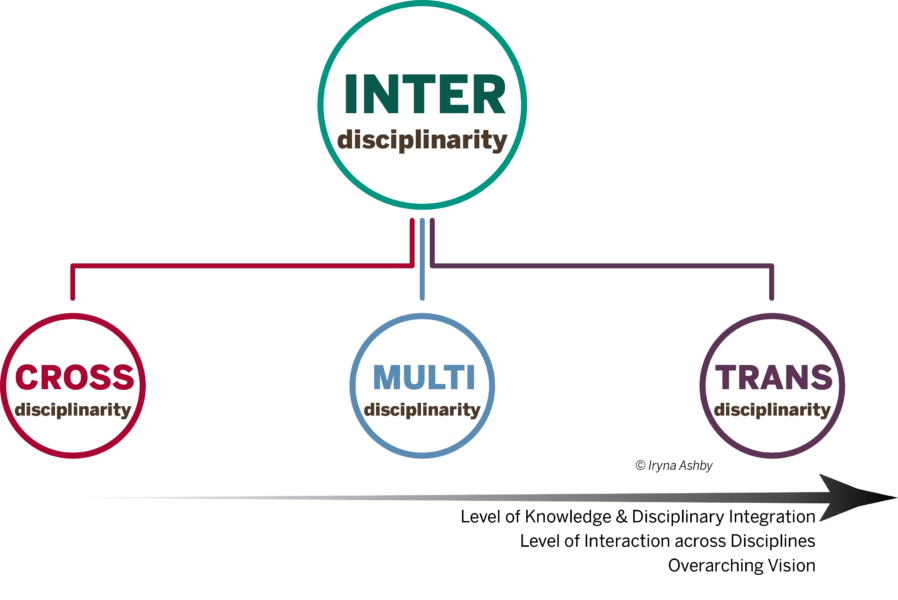

Typology of Interdisciplinary

“Interdisciplinary” refers to any type of activities that traverse the boundaries of traditional disciplines. We consider interdisciplinary being an umbrella term for three main types, including cross-disciplinary education, multi-disciplinary education, and transdisciplinary education.

Interdisciplinary Learning Outcomes

Certain learning outcomes may be more necessary to assess in interdisciplinary programs due to their integrative nature. These learning outcomes make up the defining characteristics of IDPs that interdisciplinary scholars agree should be the focus of interdisciplinary curricula: Disciplinary grounding. Defined as "the degree to which student work is grounded in carefully selected and adequately employed disciplinary insights," (Mansilla & Duraisingh, 2007) i.e., selection and application of knowledge. Students demonstrate enough depth of knowledge to "reflect on the nature of disciplines and make meaningful connections" (Borrego & Newswander, 2010).

Disciplinary grounding. Defined as "the degree to which student work is grounded in carefully selected and adequately employed disciplinary insights," (Mansilla & Duraisingh, 2007) i.e., selection and application of knowledge. Students demonstrate enough depth of knowledge to "reflect on the nature of disciplines and make meaningful connections" (Borrego & Newswander, 2010). Integration. The ability to synthesize and apply theoretical and practical perspectives from multiple disciplines to develop an understanding of complex issues.

Integration. The ability to synthesize and apply theoretical and practical perspectives from multiple disciplines to develop an understanding of complex issues. Critical thinking & problem solving. How do interdisciplinary approaches contribute to the development of these skills in ways that are different from single-subject approaches? In an IDP, it should be clear that the development of these skills require viewing "the approaches, products, and processes" of relevant disciplines from a "detached and comparative viewpoint" (Toynton, 2005).

Critical thinking & problem solving. How do interdisciplinary approaches contribute to the development of these skills in ways that are different from single-subject approaches? In an IDP, it should be clear that the development of these skills require viewing "the approaches, products, and processes" of relevant disciplines from a "detached and comparative viewpoint" (Toynton, 2005). Collaboration and communication. Language and terminology are commonly cited barriers to interdisciplinary work (Fry, 2001; Gooch, 2005; Repko, 2008). How do interdisciplinary groups find common ground and jointly construct a path forward?

Collaboration and communication. Language and terminology are commonly cited barriers to interdisciplinary work (Fry, 2001; Gooch, 2005; Repko, 2008). How do interdisciplinary groups find common ground and jointly construct a path forward? Critical awareness. "An attitude for learning that recognizes disciplinary truth and knowledge is susceptible to influence, and is also a method for analyzing benefits, challenges, and shortcomings of one's own research" (Borrego & Newswander, 2010). Can refer to reading with a critical eye, understanding errand and premises regardless of the field a text emanates from (Anderson & Kalman, 2010).

Critical awareness. "An attitude for learning that recognizes disciplinary truth and knowledge is susceptible to influence, and is also a method for analyzing benefits, challenges, and shortcomings of one's own research" (Borrego & Newswander, 2010). Can refer to reading with a critical eye, understanding errand and premises regardless of the field a text emanates from (Anderson & Kalman, 2010). Reflection. How well can students recognize and distinguish between different practices? Reflection includes "both externalizing one’s own understanding and knowledge and consciously and actively pursuing trying to see things from another perspective" (Vuojarve et al., 2022).

Reflection. How well can students recognize and distinguish between different practices? Reflection includes "both externalizing one’s own understanding and knowledge and consciously and actively pursuing trying to see things from another perspective" (Vuojarve et al., 2022).Contact

Office of Institutional Assessment, Research and Planning

5201 University Boulevard, Sue and Radcliffe Killam Library 434, Laredo, TX 78041-1900

Phone: 956.326.2275