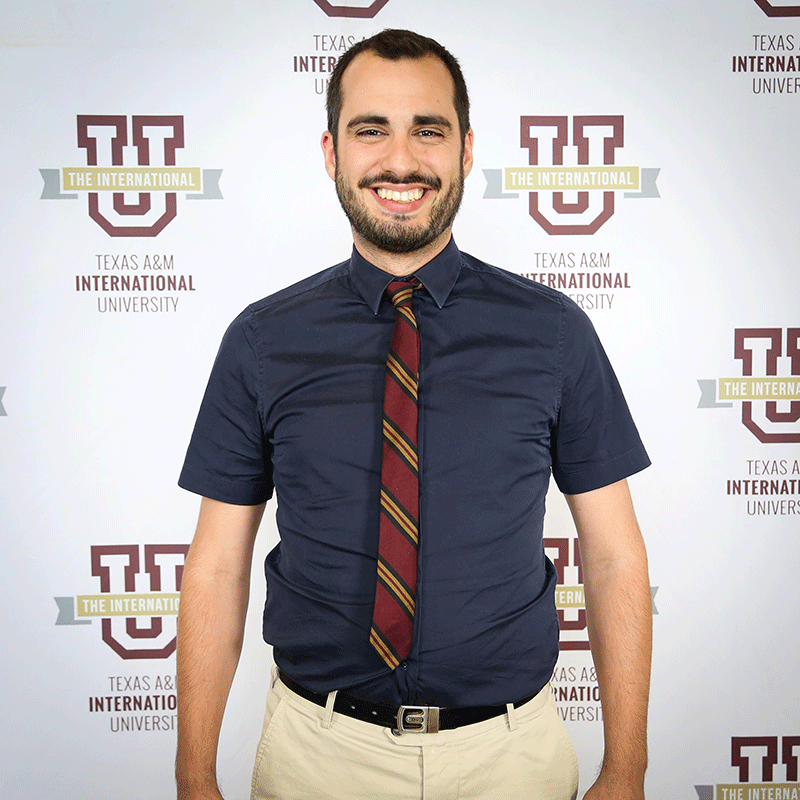

Dustdevil Diversity Spotlight: Dr. Aaron Olivas

This is part of a series highlighting diversity and inclusion at TAMIU. On the occasion of Hispanic Heritage Month , this interview features Dr. Aaron Olivas, TAMIU associate professor of History.

Sharing History and Promoting Diversity

Tell us about yourself, where are you from and what you do here at TAMIU?

I was born and raised in Stockton, California, which is consistently recognized as one of the most diverse cities in the entire United States. That diversity has had a tremendously positive impact in shaping my education as well as my general outlook on life. My family is also multicultural: Mexican on my father’s side and Iberian (Spanish) on my mother’s side.

My experiences as a member of both of these ethnic communities definitely led me down the path to become a historian of the global Hispanic world. It not only piqued my curiosity to learn about the past experiences of my ancestors (often ignored by teachers before I went to college), but also to combat many of the stereotypes I have had to endure since I was young (which sometimes persist to this day in the United States). This very personal connection between my family background and my research is reflected in my teaching at TAMIU, where my history courses focus on both Latin America and Spain.

When did you join TAMIU?

I began teaching at TAMIU as an assistant professor of history in August 2014. I was promoted to associate professor at the beginning of the current 2020 academic year.

Tell us about your experience living here and familiarizing yourself with the Laredo community.

It’s funny how there are certain aspects of Tejano/Norteño life that totally remind me of childhood moments, especially particular sounds, smells, and tastes that I associate with my father’s side of the family. Of course, this makes sense because my grandparents and great-aunts and -uncles on that side were all raised in South Texas. Still, before coming to Laredo, I lived in Los Angeles for nine years for my Ph.D. and postdoc at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

Given recent trends in immigration, I became more accustomed to the culture of Southern México. Above all, Oaxacan culture is now so prevalent in California but also extremely different from that of Northeastern Mexico. But it’s the little things in Laredo like the local accent, flour tortillas, certain salsas at Taco Palenque or Tacolare, and even the peculiar way people laugh around here that make me think of Grandma Juanita, Great-Aunt Cuca, or Uncle Chuy. Living here makes me feel like I’m returning to some of my family’s roots. I can better understand my grandparents to some extent now. On the other hand, I’ve also been quite surprised and lucky that H-E-B sells authentic chorizo and jamón from Spain, which my Great-Aunt Rose would approve of since it’s from Salamanca. They usually carry the correct wine (Ribera del Duero) and olive oil, too. I have no idea who else is buying these things, but they’re what I need and you can’t find them just anywhere.

Can you share about your research interests and how you became interested in your area of study?

I’m most interested in the socio-political culture of the Iberian Atlantic World, above all trans-imperial relations and the integration of Spanish colonial subjects into the politics of Early Modern European empires. Rather than marginal or passive figures, creoles, mixed-race, and indigenous communities were highly aware of global geopolitics throughout Latin America’s Middle and Late Colonial periods (17th and 18th centuries). My current book project analyzes this phenomenon during the transition from Habsburg to Bourbon dynastic rule over the Spanish Empire. The shift to the new dynasty led to the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession (1700 - 1715), one of the first truly global wars.

While the conflict inspired certain colonial elites to actually challenge Spanish royal authority, others used it as an opportunity to renegotiate their privileges or even reorient power dynamics between the Americas and Europe. On top of that, my research further reveals how colonialism played a central role in late 17 th - and early 18 th - Century European politics by considering Spanish, French, Dutch, and English preoccupations with loyalty to the Bourbons in Colonial Latin America. I focus especially on the role of French cloth merchants, ministers of state, and slave traders (agents of the Compagnie Royale de Guinée) in fostering loyalty to the Bourbons across the Atlantic and combating the dynasty’s enemies through the Asiento (colonial slave monopoly).

I first became interested in this topic when I was a masters student at the University of Chicago. At the time, I was digging through Mexican colonial manuscripts at the Newberry Library when I stumbled across some 18th - Century cabildo records from outside México City. The records dealt with news from Madrid that the Bourbon monarch had been forced to abandon the capital to the army of the Habsburg allies. I was surprised how quickly and urgently the crown communicated this information to what amounted to be a provincial town. That made me curious how the town council would have responded to such shocking news. Would they have continued to be loyal to the King? Or would this have been an opportunity to rebel? At the time, I was working on a completely different project, so I set these questions aside. Although I originally intended to work on gender and informal power in the Spanish Empire as a Ph.D. student, I ended up going back to those manuscripts and then discovered others on the same topic at archives in México, Spain, and France. As I found out, even the most peripheral communities were totally aware of (and entrenched in) the Spanish succession crisis. And as it turns out, there was so much to gain or lose as a consequence. Otherwise, most historians assume that the event was inconsequential to the everyday lives of colonial subjects.

How do you feel your contributions impact TAMIU, the community and world around you?

TAMIU students seem to appreciate my perspectives as well as the overall subject matter that I teach. For many, this is the first time they’ve ever engaged with Latin American or Spanish history in the classroom. It pleases me immensely that this material interests them. It makes me feel like I’m doing something right.

Who has been your greatest inspiration and why?

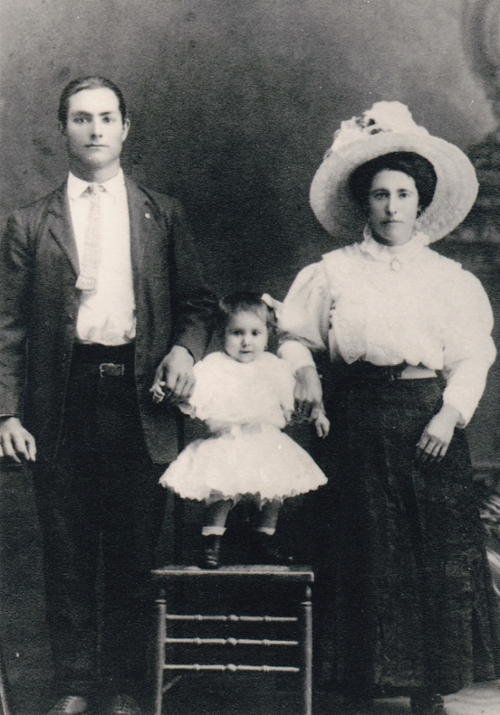

My great-grandparents from México and Spain are my greatest inspiration. When I was younger, I used to consider my grandparents to be my greatest inspiration. Both sets of grandparents were first-generation Americans. But they were very humble people and didn’t really see themselves as exceptional. Instead, my grandparents themselves always looked up to their parents, and thus they convinced me to do the same.

Both sets of my great-grandparents immigrated from México and Spain at roughly the same time (the 1910s). On my father’s side, they were Mestizo and Yaqui immigrants from Northern México (Ojinaga, Chihuahua and Monterrey, Nuevo León) who settled in Eagle Pass and Crystal City. The Olivas family were refugees of the Mexican Revolution, having sided with the faction of Pancho Villa (one of the losing sides of the war). On my mother’s side, they were Iberian immigrants from Central Spain (Bóveda del Río Almar, Castilla-León and Cilleros, Extremadura) who settled in California after cutting sugar cane in Hawaii. They were escaping hunger at the time, and once they got on their feet, they did their best from the United States to help their family members back in Spain get through the trials of the Franco dictatorship. Both sets of great-grandparents faced immense adversity and made the most incredible sacrifices to survive. Yet they remained resilient throughout their lives and never forgot where they came from.

Please share your proudest accomplishment to date.

My proudest accomplishment was marrying my husband Luis in 2015. Now I’m unofficially Guatemalan (according to his Grandma Santos). Also, I’m very proud to be the uncle of four nieces (Izabella, Kassie, Ava, and Alexandra) and one nephew (Marino). I’m equally proud to be the godfather of my cousin Sofía and niece Ava.

Tell us what you’re doing today academically, career of life-wise and what your future plans are.

Right now, I’m preparing to present research at an international colloquium commemorating the 500th Anniversary of the Conquest of México. It’s organized by the Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez (Chile) and the Universidad de Alcalá de Henares (Spain). My “virtual paper” will deal with reinterpretations of the Conquest through the lens of European Baroque and Enlightenment culture. In particular, I analyze the craze of staging Conquest-themed operas in Italy and France during the 18 th - Century. Besides offering stunning music, I argue that such operas also provide entertaining critiques of absolutism. The colloquium complements an upcoming volume (University of Oklahoma Press) edited by my colleagues Peter Villella and Pablo García Loaeza. Like the colloquium, the volume’s various chapters bring together experts in the fields of Mexican, European, and U.S. history to reflect upon how and why the Conquest has taken on different (and often unexpected) meanings for different global audiences over these past five centuries.

What are some of the aspects of your culture or tradition that you celebrate or appreciate the most and how meaningful are they to you?

I feel as though I’m celebrating my culture every time I step into the classroom. That’s been a blessing because I’m teaching nine months out of the year. It’s common for me to grab objects from around my apartment and lug them to campus. I’ve collected all sorts of artifacts—some from the past, some from the present, some replicas—that directly relate to the subject matter that I teach. I enjoy when students touch, interact with, and respond to these objects. It makes our shared past seem more real. Students are often surprised that I own these things. I’m not going to reveal here what those objects are. You’ll have to drop by one of my classes if you want to find out. I should add that Killam Library Special Collections and Archives has also been extremely generous these past six years in giving me another forum to share my passion for history with the public.

Otherwise, I’ve really enjoyed celebrating Holy Week each spring in Laredo. Easter has always been my favorite holiday for several reasons: childhood barbecues on my grandparents’ ranch in Northern California; my Jesuit and Salesian education (middle school, high school, and college); and four amazing Easters that I was lucky to spend in Seville, Salamanca, and México City (with their spectacular processions and even flaming Judas effigies). The celebrations in Laredo seem to bring back those memories. There’s also a family from Nuevo Laredo that crosses over to sell braided palms each year. I was never able to bring those back to the United States from Spain or Mexico. In fact, on the same day that Dr. Pablo Arenaz called me on the phone to let me know I got the job at TAMIU, I remember passing a street vendor in Barcelona with incredible braided Palm Sunday palms, and I had thought to myself “I wish I was able to carry one of those back home to the States.” But now I can get a version of those here in downtown Laredo.

In your opinion, what are some of the notable contributions by people in the culture or traditions that you represent?

At the moment, my sister Andrea is working as a pathologist at the University of Chicago Hospital trying to find a cure for colon cancer. If I’m going to give somebody with my same background some credit, it’s going to be her. And I know my sister also values the culture, work ethic, and courage that we’ve inherited from our Mexican and Spanish families. She’s also saved many lives as a surgeon in Chicago and San Francisco. As my Great-Aunt Rose once put it, that makes all the hardship, sacrifices, and humiliation that her immigrant Spanish parents had to go through totally worth it in the long run.

I recognize the contribution of my Great-Uncle Richard López, who was a Chicanx civil rights leader in Crystal City, Texas and Stockton, California between the late 1920s - early 1990s. He fought against discrimination not only for the Latinx community, but also the Black and Filipinx communities as well. His career is a reminder how our struggle is the struggle of others and vice-versa.

How do you think they can continue to increase their visibility and impact here and in the world?

People of Latinx, Hispanic, or Chicanx descent should vote, vote, and vote! Of course, this is deceptively simple. It’s mind-boggling how many hurdles are put in place in this country in order to make voting inconvenient, so it’s understandable why a considerable percentage of the Latinx community isn’t always represented in the ballot box. But I have hope that this can (and will) change. I would also urge voting with empathy. By this, I mean not letting ethnic and gender stereotypes that have historically been a part of certain Latinx worldviews contribute to the oppression of others in and outside our cultural community. Here I’m referring to specific types of colorism, racial attitudes (typically against people of indigenous or African descent), machismo, and even homophobia. Let’s call this decolonizing your vote!

Is diversity important at university campuses, in the workplace and overall? Why?

Of course, diversity is important—everywhere! Everyone should strive for and cherish living in a diverse community. Everyone should listen to a plurality of voices in their everyday lives. I’m still puzzled why more people in this country or elsewhere haven’t realized this already! Being around people of different ethnicities, genders, ages, and opinions is the best way to learn in life. If in the process you find that you’ve been wrong or unfair to others, change. If in the process you discover that someone you didn’t realize needs your help or support, help or support them. If in the process you find that you’ve been ignored or that your side of the story hasn’t been told, speak up. You cannot truly learn and improve yourself without listening to and communicating with everybody else. Otherwise, you might as well go live on a deserted island.